About 10 years ago, I became an assessor for funding agencies. I have since worked for AHRC, Innovate UK, EIT and EU programmes to help them assess funding applications. As a result I spent a lot of time looking at other people’s (sometimes terrible) spreadsheets and it’s become a bit of an obsession. I’ve often started a project, quietly wondering: what spreadsheet could we make to help with this problem? I’ve also opened documents, emails and Miros thinking to myself: could this have been a spreadsheet instead? Often the answer is yes. Here are some reasons why I think they’re important.

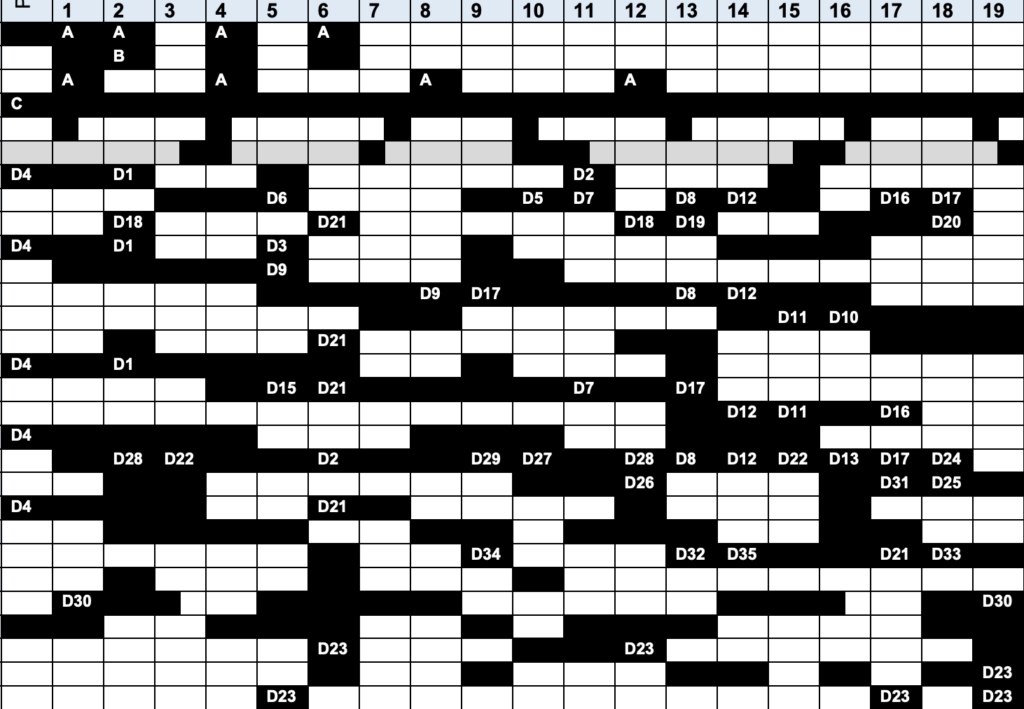

- ‘First to Gantt’ principle. Google Sheets and Excel can be a perfectly acceptable place to craft a story about people’s time, dependencies, deadlines, and other actions on a project. It’s not so much a question of when you make a Gantt but how quickly you can put one together and give it to your project/delivery manager/sales team. It’s a race against time because being the last one to comment on a Gantt probably means the changes you’d like to see aren’t going to be implemented. It’s like being the last to comment on a long doc: everybody is tired and nobody cares what you think unless you’re their boss. So if you’re the first one to put a Gantt together, you set the shape of the project. Others might tweak it, but they’ll mostly be grateful you’ve taken that task off their hands.

- Us vs. Them In design circles, spreadsheets are associated with sales and finance. In other words, the ‘eww’ part of a business. No matter whether for profit or a charity, every business has costs. Ignoring the broader financial realities of a business as an employee is both a privilege and a mistake. If you don’t have an understanding of what motivates your finance and operations team, their decisions won’t make sense to you. They just happen to communicate using spreadsheets. It’s not to say spreadsheets are a mirror of an organisation but if someone is going to use a spreadsheet against you as a designer, you might as well learn to defend yourself. Johnny Martin’s class at the British Library is a great place to start.

- Everyone wants to see the sausage being made. Up to a point. A financial spreadsheet is rarely work in progress for very long. Monthly data gets collated, the end of the quarter rolls around, the quarterly review happens, decisions are made. The spreadsheet grows another tab for Q4 and at the end of the year, yearly numbers are collated in the first tab. A spreadsheet rarely grows on forever. Another one gets created for the new year but we all know what form it’ll take. There’s repetition, comparison, decisions embedded in the process of creation. In comparison, I’ve seen 100+ slide presentations, 100+ page reports, Miros that are an amalgamation of a year’s worth of workshops and other digital follies. These assets are impossible to digest unless there’s an executive summary or someone walking you through it in Prezi. They lose their ‘raison d’être’ quickly. In comparison, the financial spreadsheet has become not only self-standing but easily legible to a larger number of people in and outside an organisation which is why ledgers are still archived. I think there’s a lot to learn from this in the assets designers not only produce but hold on to and reuse. What kinds of new visual standards can we create and set in work culture with the plethora of new tools that have emerged?

- Having a spreadsheet doesn’t mean you’re not creative Spreadsheets feel weird because they don’t require traditional levels of visual creativity but they can be the touchpoints for some interesting visual and process-centric problem solving. During the pandemic, I worked with some very talented A/V folks who were barely literate. I came up with a spreadsheet we could use for border declarations while my project manager got my colleagues to use a barcode scanner when they were packing pallets of A/V kit in the basement, filling another spreadsheet. This allowed us to run a multi million pound account on 2 spreadsheets we tweaked for every European shipment. I consider this as much an act of design work as anything else I’ve done in my career.

I think there’s a lot more I could say and I wish I could breach a lot of NDAs to share more findings but you can see where I’m going with this. I’d love your thoughts in the comments if you have any (especially if you think I’m wrong).

One thing I’ve noticed “First to gantt” doesn’t have as much sway in firms that are running more on agile / engineering-centric cultures?

Spreadsheets, actually MS Excel, is so ubiquitous do you assume everyone can use it? I certainly do.

I love the First to Gantt principle as well as “if someone is going to use a spreadsheet against you as a designer, you might as well learn to defend yourself”. I extrapolate that to “Excel, PowerPoint, Word are the AK47s of corporate warfare.” Going even harder, is Teams “mutually assured destruction (distraction)”?