It’s been almost 3 years since I wrote Smarter Homes but my interest in the historical role of the home in our communal and societal decision-making hasn’t stopped. After working as Head of Labs at Bulb and doing research for Overlay (by ING Labs) I got really interested in the more administrative side of homes. Mark Simpkins and had come up with databrick in 2016 so when Chimni and xbim reached out to run a little workshop about this side of things, it was a no brainer.

These are some notes on what I’ll be sharing at the IoT Meetup at Hardware Pioneers Max, the night before the workshop which is on Friday this week on Zoom.

Information myopia

If COVID-19 has reminded us of anything it’s that personal action often has a collective consequence and vice versa. The degree to which we acknowledge this consequence is what sometimes divides people. Within the home, the consequence of taking long showers, putting a wash on in the evening between 4-7pm or charging your EV in the daytime is not immediately obvious. Your bills might be higher but you’ll only find that out later on. We constantly feed a kind of second self as the author Olga Tokarczuk would put it. Our second self has an impact on the National Grid mix, slave labour in Asia and fossil fuel production. Things happen out of sight, and out of mind, but they do happen.

We are no longer as literate as we used to be about the systems that support our homes because we’ve been able to build industries that service those homes quickly. In the 1920s, at the beginning of mass electrification, women were trained by the EAW to change fuses and understand how they were wired. Promotional tea towels were even printed with the diagrams. I wonder how many of us know that much about our electrical layout, the exact age of our boiler, what the right temperature is for a room, how old our home actually is or who has done what to it over the years.

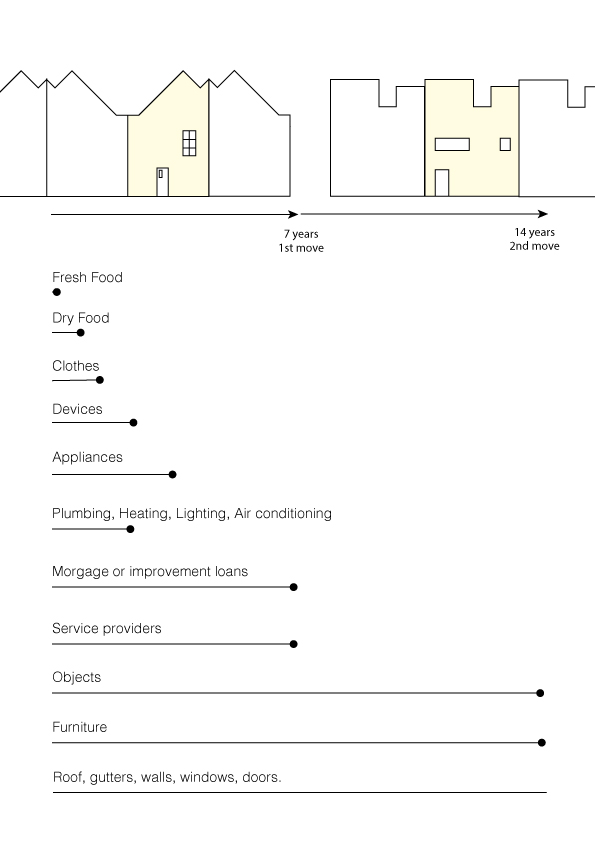

With the churn in London around 7 years (irrespective of whether a household own or rents) and 14 years outside of London, there’s plenty of reasons why people don’t spend more time learning about, caring for or repairing their home. Their home improvement horizon, if we can call it that, is constantly interrupted by life events like a partner that moves in, a child on its way, a elderly parent who needs care. Life literally gets in the way and non-cosmetic improvements are treated as a game of ‘pass the parcel’.

And then there’s the power structures of capital and convenience that act on the home indirectly. A badly insulated home doesn’t translate into anything other than higher bills for tenants who have no power to improve the property and higher bills might mean little for a middle class person whose energy bills are well below 10% of their monthly outgoings and paid on Direct Debit.

The failed green homes scheme isn’t only about bad program design, but also about financial realism. Most of the big improvements like changing windows or insulating walls cost well over £5K but almost 1/3 of people have less than £1.5K in savings so how can we ever expect people to prioritise this?

Of course things would change dramatically if the law made it illegal for someone to sell a house they didn’t improve while they owned it. Or a valuation industry that actually downgraded homes that had an EPC rating below C. Mortgages might not be available to people whose property is poorly performing either. Oh and could someone please reduce the list of exemptions to getting an EPC certificate done? Those would be such blunt instruments the real estate sector would never recover. Which is why it’s never going to happen.

So what then?

Data in lieu of policy-making

Sometimes, a politically difficult problem can become easier to act on when understood with data. Air quality is a little like that. Years of seemingly pointless pilots followed by the panic of COVID-19 and LTNs that now actively use air quality data to prove improvements.

I wonder if it’ll be like that for smart home devices and logbooks (some call them home passports). Having a digital life for a home doesn’t have to mean sharing data about the people in it. It might instead mean gathering all the information that different public and private bodies already hold about a home and making it accessible and machine readable. From the date of energy improvements, guarantee certificates for the work, the name of tradespeople responsible for repairs, the yearly cost of utilities, lots of information can be collected once a year, anonymised and presented in a way that makes sense to the largest number of actors. A Dopplr report for the home that’s online and actually useful.

If it worked for EPCs, surely it’s worth doing for other aspects of home living, caring and repairing. Whether smart thermostat, flood sensors, water meters and smart meters all feed into this, I don’t know. I think they should but it’s not essential. Most homes don’t have them and most people just want to see a pretty visualisation of their home like in The Sims or Minecraft and be able to make decisions effectively and keep information updated easily.

This digital, open, logbook might not be politically important straight away but, very soon, it will. Happy storm and flood season everyone. I mean Happy Christmas.